Some of Michael’s early stallions brought six figure prices and had million dollar stallion careers. The next important stallion had a humbler beginning. Charlie Degas, the purebred Percheron foaled in 1973 became the foundation stallion of the Stonewall Studbook and an important influence in the development of the Stonewall Sporthorse.

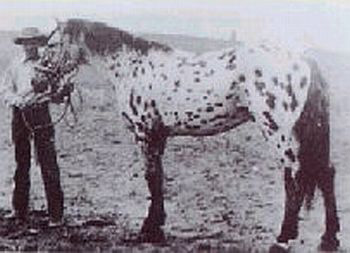

Charlie Degas was the product of a noted Percheron breeding program in Ohio with strong Canadian influences. He was sold as a weanling and began a show career in the southeast where he became a grand champion in hand and began a successful career as a stallion. Over the years he changed hands several times, coming West and his fortunes declined. In the fall of 1989 he was brought looking battered and beaten beyond his sixteen years to an auction by a disreputable horse trader.

He attracted no attention from potential buyers. Michael was not in the market for a new stallion but kept returning to gaze at this forlorn horse. There was something about him that spoke of a noble past. His exceptional quality was apparent if you could look past the dull hair coat, ribs showing and tattered mane and tail. The sole bidder was the killer buyer at about 50 cents a pound. A noted Percheron breeder whispered to Michael, “I’ve seen you looking at that horse. I hope you know that he is a really fine stallion.” Michael raised his hand and Charlie Degas had a new home.

Brought to Winters, California, Charlie Degas blossomed and plans were made put him to stud. His first crop for Michael surpassed all expectations. The Stonewall Sporthorse was born and Charlie Degas entered the stud book as F-#1. Mated to a daughter of the world champion and leading sire, Apache Double, Charlie sired Stonewall Baby Jane, who in turn produced the stallion Stonewall Rascal. Baby Jane’s full brother was named Stonewall Rebel and he, too became a successful stallion in a brief but ill-fated career. His first foal was Stonewall Scarlett, a daughter of Stonewall Crystal. Rebel’s tenth and final foal was Stonewall Domino, a son of Dona Francisca.

HYBRID VIGOR

Some people have questioned whether the Stonewall Sporthorse can be considered a true “breed”. Over the past fifty years we have crossed several breeds to create what has come to be known as the Stonewall Sporthorse. We have always maintained that our selected crossing of breeds has been carefully designed to create a desired result. We have achieved a consistent type, brimming with vitality and strength due to hybrid vigor. There are many examples of this in recognized breeds of horses. Most modern European Warmbloods, Quarterhorses, Appaloosas and many others have been created and improved by crossing two or more breeds. We believe there are more breeds of horses today that are the result of crossbreeding than there are intensely pure breeds such as the Thoroughbred, the Arabian and the Friesian which have studbooks long closed to any crossbreeding.

CROSSBREEDING is the result of breeding two individuals of different breeds. This achieves a high degree of hybrid vigor. HETEROSIS, or HYBRID VIGOR is the improved or increased function of any biological quality in a hybrid offspring. An offspring exhibits heterosis if its traits are enhanced as a result of mixing the genetic contributions of its parents.

OUTCROSSING is the breeding of two individuals without a common ancestor for at least four generations. This is the breeding practice we have followed for many years in the Stonewall Studbook. Outcrossing achieves the highest degree of genetic diversity and avoids inheriting defective genes from a common ancestor.

INBREEDING concentrates an ancestor’s genes by breeding two related animals together. This increases the influence of a highly desirable individual in the pedigree. It helps to increase the chances of inheriting the superior characteristics of that ancestor, but it comes with the risks of inheriting genetic weakness or defects as well. For each generation forward from a common ancestor, the influence is diminished by half. Inbreeding is the practice of mating two individuals with a common ancestor, usually within the first four generations. Inbreeding increases the influence of that common ancestor, usually an exceptional individual whose qualities the breeder attempts to preserve and enhance.

The downside of inbreeding is the marked possibility of doubling negative genetic characteristics, anomalies or mutations with disastrous results. When inbreeding is successful, the resulting foal can strongly resemble or replicate the achievements of the ancestor to which it is inbred. When it fails, the resulting foal can inherit negative characteristics that can render it worthless.

Inbred individuals often exhibit disposition problems, conformation faults and reduced fertility. Successfully inbred horses, on the other hand, can demonstrate marked prepotency as sires or producers due to their concentrated gene pool.

In modern practice, the closest form of inbreeding is “2 x 3”. In other words, the same individual will appear in the pedigree in the second and the third generations. For example, a son of Northern Dancer will be mated to a granddaughter of Northern Dancer to produce a foal inbred 2 x 3. Inbreeding 3 x 4 to an exceptional ancestor is commonly done, rarely with any negative genetic complications.

Linebreeding is a form of inbreeding that can repeat the same individual in a pedigree three or more times. Linebreeding can also refer to a very close form of inbreeding, such as father to daughter, or “1 x 2”. An exceptionally close form of linebreeding would be to mate a stallion to his daughter, then mating that same stallion to his resulting daughter/granddaughter (1 x 2 x 3). Another close form if linebreeding is the mating of full siblings. The same stallion appears as grandsire twice, as well as the same mare appearing as granddam twice (2 x 2 x 2 x 2). This close inbreeding intensifies the influence of the desired ancestors, but can be fraught with genetic peril.

Although I have not personally practiced inbreeding, the most successful stallion I have owned is the multi-millionaire, world champion Apache Double. Apache Double was produced by the intensely inbred mare Runaround, a daughter of Apache 730 produced from a daughter of Apache 730, or inbred 1 x 2. Some breeders would credit Apache Double’s remarkable success as a stallion, and his exceptional prepotency, to his closely inbred dam.

Another individual I owned at that time was the mare Arbol’s Fancy whose sire was intensely linebred to the stallion Morgan’s Leopard.

Geneticists maintain that the ultimate in hybrid vigor is achieved by mating two inbred but unrelated individuals together. An example of this practice resulted in Stonewall Dottie West, when Apache Double was mated to Arbol’s Fancy. The resulting mare, Stonewall Dottie West, appears prominently in the pedigrees of modern Stonewall Sporthorses. Her powerful influence through the years can be attributed to her abundance of hybrid vigor and concentrated gene pool.